The Great Rift Valley is the largest rift system on Earth, stretching about one-sixth of the Earth’s circumference. From satellite images, it appears as a massive scar, earning it the nickname “Earth’s Scar.”

In Kenya, the rift’s outline is very clear, slicing through the country from north to south and intersecting the equator that runs across the nation. This gives Kenya an intriguing nickname—the “Cross of East Africa.”

Standing on the observation deck, you can see the rift’s sheer cliffs and rolling hills, like towering walls on either side. Looking out, the valley floor is lush with evergreen vegetation and seemingly bottomless. Dormant volcanoes dot the landscape like scattered marbles, and lakes glisten like sparkling gems.

In this “Earth’s Scar,” which ranges from a few dozen to 200 kilometers wide and 1,000 to 2,000 meters deep, the fertile soil created by the rift’s volcanic activity supports rich pasture and dense forests, making it Kenya’s famous agricultural region known as “Rift Valley.”

Lake Naivasha, located at the rift’s base, is Kenya’s only freshwater lake. Boarding a boat, you can enjoy the serene lake views and surroundings… Everything here—lake, light, mountains, and colors—feels effortlessly and subtly perfect.

The boatman tossed a fish hoping to capture the dramatic moment of a fish eagle hunting, but the eagle perched high on a branch, barely glancing at the small fish and shrimp. Water birds stood on the water’s edge like living paintings. Gentle hippos lounged in the water, with their family coming ashore to graze. Various unidentified birds either perched or flew around, unfolding a series of natural scenes before us.

The boat took us to a small island in Lake Naivasha—Crescent Island. The entire island is a small volcanic crater partially submerged under the lake. The part of the crater that is underwater is not visible, but the remaining half has the shape of a crescent, hence the name “Crescent Island.”

The island’s locals guided us on a hike around Crescent Island. On the expansive grasslands, we saw dazzling acacias, ever-blooming bougainvillea, and spiky trees draped with climbing vines. We spotted the “Special Five” wild animals: the Grevy’s zebra, reticulated giraffe, Maasai giraffe, East African kudu, and Somali ostrich.

On safaris in Kenya’s national parks, no one is allowed to get out of the vehicle. However, on Crescent Island, you can get up close to the animals and take photos, making it a unique experience. Just remember to be quiet when approaching them, so everyone on the island remained silent while searching for animals.

Only the goofy giraffes seemed unbothered. There are five giraffes on the island, including two calves only six months old, already standing 2 meters tall. Watching them graze with their large double eyelids, long lashes, and silky coats is just adorable!

Why are there so many animals on Crescent Island? Our guide, Luo, explained that Crescent Island was one of the filming locations for movies like “Tomb Raider,” “007,” “Out of Africa,” and some African documentaries. The animals were airlifted from Masai Mara and have since lived here for generations. Only herbivores are found here, and while the environment is simple and lush, being exiled to a solitary island might be considered both a blessing and a curse.

Mombasa

Mombasa’s Old Town is famous for Fort Jesus. This 16th-century Renaissance fortress, built by the Portuguese, stands 18 meters high and covers an area of 15 square kilometers on Mombasa Island. It guards the natural harbor of Mombasa, controlling the sea route to and from the Indian Ocean. Naturally, it was a key strategic location during the colonial era.

For centuries, the Portuguese, Persians, Arabs, and Brits have fought over Mombasa, each leaving their mark on the city. In Swahili, “Mombasa” literally means “City of War.”

One of Fort Jesus’s key roles was to serve as a major port for merchant ships entering East Africa from the Indian Ocean. The old streets adjacent to the fort are a testament to thriving trade and were home to Swahili, Arab, Portuguese, and British settlers. Today, this area is a major tourist destination in Kenya due to its rich cultural and historical heritage.

Walking through the winding alleys of the old town, it’s hard to imagine the battlefields of the past. What you see now is a blend of Eastern and Western cultures, North and South architecture, and various world religions. You hear the sound of weaving looms and the creak of wooden cart wheels, and smell a fusion of flavors from diverse cuisines. It’s no wonder that Mombasa’s old town has earned the title of a UNESCO World Heritage site.

As the sun sets, Fort Jesus and the old town of Mombasa bathe in the twilight. The worn, crumbling buildings and the everyday lives of the people intertwine, with historical remnants casting shadows of the past, yet always moving forward.

Maasai

If “cultural differences” drive our exploration of the world, then the Maasai village in Kenya’s Masai Mara is undoubtedly one of the closest encounters with primitive culture.

Maasai men carry three essentials when they go out: a sword, a club, and a walking stick.

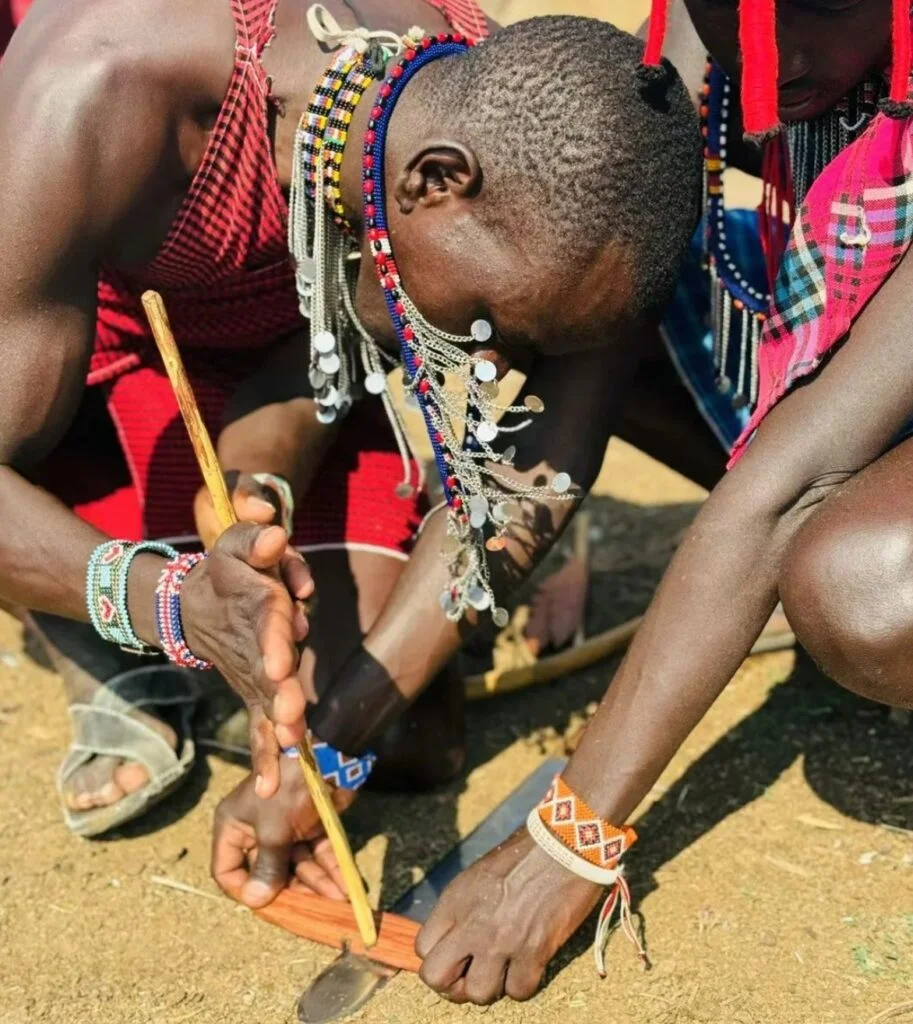

The history of the Maasai people dates back 5,000 years. While we have moved through primitive, agricultural, and industrial societies and now live in a modern digital age, the Maasai still practice traditional ways—starting fires with wood, pastoralism, hunting, building mud huts, living without water or electricity, and adhering to a patriarchal, polygamous society. They continue to rise with the sun and rest at sunset, living in harmony with animals and sleeping under the stars.

Departing from Naivasha, we drove 6 hours to the Masai Mara. After a brief hotel check-in, we headed to a Maasai village just a short drive away. As soon as we parked, a few Maasai men dressed in traditional red shúkà (cloaks) approached us. With their dark, rugged faces, swords, and Maasai clubs—one end thick, the other thin, used to ward off wild animals—they looked both unfamiliar and fascinating.

The village is surrounded by a large circular fence made of thorny bushes. Inside the fence, there is a ring of mud huts, and the center is an open area. Every night, the villagers block the village gate with dry branches and gather their cattle in the center. They themselves stay in the small mud huts, sleeping on cowhide.

When a Maasai person blows a horn, the Maasai in the village gather at the gate and start dancing. A chant, reminiscent of Buddhist scriptures, begins, and the men rhythmically shake in a single motion. It resembles both a prayer ritual and a display of power meant to intimidate animals.

After the welcoming dance, the Maasai men line up and start jumping upward. I had done some research beforehand and knew that high jumping is a Maasai tradition. They believe that the higher you jump, the closer you get to the sky.

This is both a belief and a gesture of friendship. We were invited to join in the jumping, with a “you jump, I jump” spirit. Watching the video of us jumping together, I realized the difference. Their lean, strong bodies, with well-defined and elastic calf muscles, are perfectly suited for high jumps.

The Maasai man invited us into his home, a small hut made of cow dung and mud, about 2 square meters in size. It was very basic. Even in the middle of the day, the interior was dark, with only a small beam of sunlight coming through a hole near the bed. Between the two beds was a charcoal stove for cooking, and a shelf along the wall held all their household items—truly a case of “poverty in its purest form.”

We once looked down upon the violence, colonization, and invasion in the development of humanity. But on the flip side, without these events, would we still be living in an era of “rising with the sun and resting at sunset”?

Meeting the Maasai, we see what a simple yet fierce life truly looks like. All we can do is wish them well, as living according to one’s own desires is the greatest freedom of all.