After disembarking at the port of Montevideo, I walked along the Río de la Plata. The reddish tint of the water contrasted beautifully with the lush green grass, creating a picturesque landscape. This area marks the city’s edge, with a touch of rustic charm.

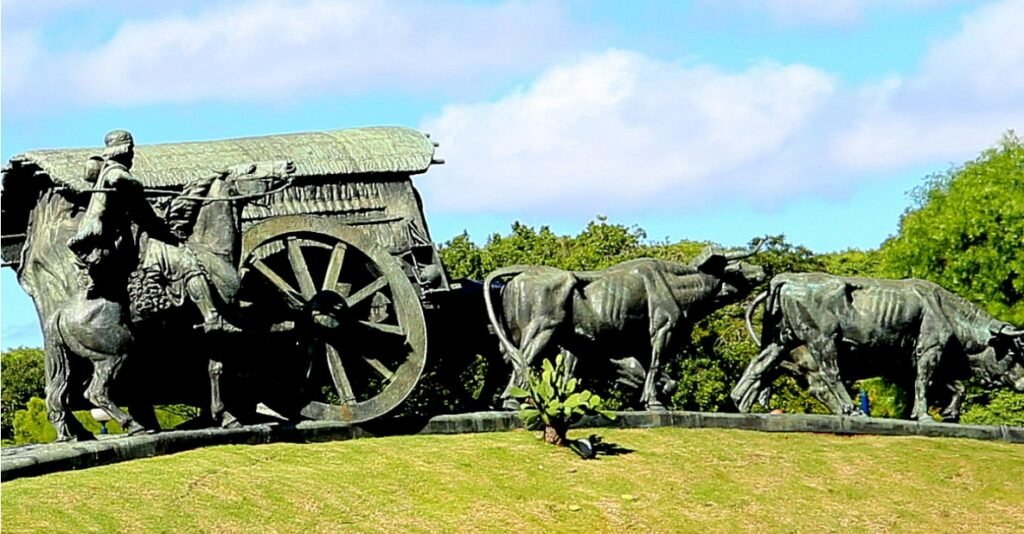

Along the roadside, I came across a bronze sculpture of an ox-drawn wagon. Six oxen pull a covered cart, with a man riding a horse beside them, reflecting the struggle of their journey. The rough wooden wheels and emaciated oxen convey a sense of hardship. This sculpture, completed in 1934 by renowned Uruguayan sculptor José Belloni, symbolizes the challenging lives of the gauchos and has been declared a national monument. The gauchos are a mixed-race people descended from Spanish settlers and Indigenous communities. The Spanish first arrived in the 15th century, and over time, the appearance of the gauchos has become indistinguishable from that of white Europeans.

Uruguay, like Argentina, is deeply influenced by European culture, with Spanish being the predominant language. The cities are filled with sculptures, street parks for leisure, quiet roadside stalls, and even historic marketplaces with over a century of history, reflecting Spanish architectural styles. These markets are lively spaces where people can enjoy coffee, shop, or dine. I saw a whole lamb roasting over a charcoal fire, though beef is the staple food in Uruguay, with lamb being less commonly consumed.

I also noticed young men drinking mate tea, holding small thermos flasks and traditional tea sets. This cultural practice is unique to the gauchos. The tea is brewed in a small pot called a mate, often lined with glass and wrapped in leather, and it is sipped through a metal straw. I bought one of these in Argentina. It is said that the Indigenous people introduced mate to Spanish soldiers to relieve hangovers, and over time it became an essential drink for the gauchos—valued not just for tradition but also for its health benefits.

Montevideo lies on the eastern shore of the Río de la Plata, a river so wide it feels almost like an ocean. On the opposite shore is Buenos Aires, Argentina, visible only in imagination due to the vast expanse of water between the two cities.

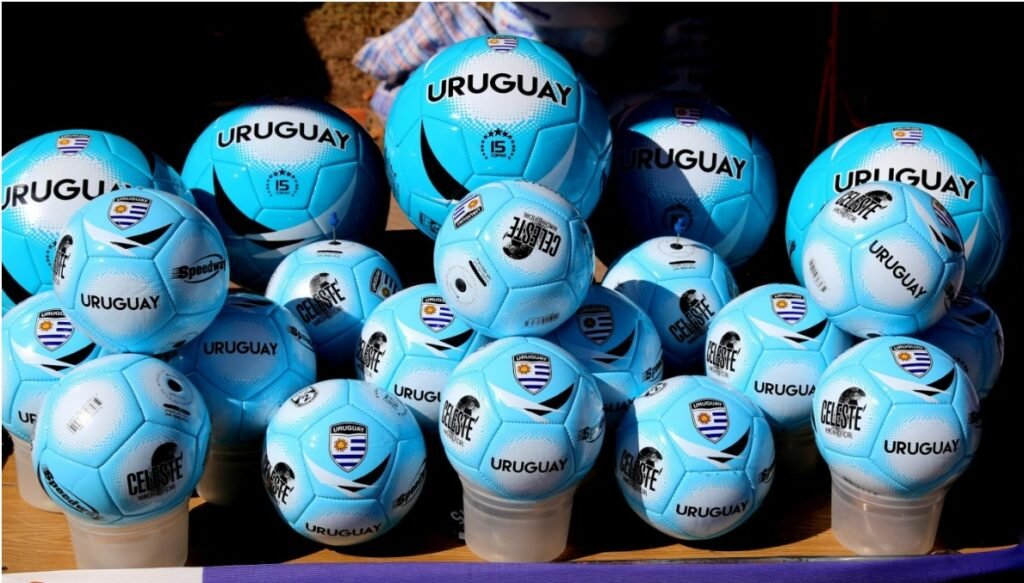

Uruguay’s football legacy is world-renowned, having won the Copa América 15 times, surpassing even the dominance of Brazil and Argentina at various points in history. On the streets, vendors sell footballs in different sizes tailored to various age groups. These footballs, beautifully crafted and neatly arranged on street stalls, add a vibrant touch to the local markets.

Along the roadside stands a bronze sculpture of an ox-drawn wagon, featuring six oxen pulling a covered cart with a horseman riding alongside. The scene vividly captures the hardships of the journey, with rough wooden wheels and the gaunt figures of the oxen conveying a sense of struggle and heaviness. This sculpture was created by renowned Uruguayan sculptor José Belloni in 1934 to depict the challenging pioneering life of the gauchos. It has since been declared a national monument by the government, reflecting its cultural and historical significance.

Uruguay’s Legislative Palace

The Legislative Palace in Uruguay is a striking example of neoclassical architecture. Its triangular pediment and square columns evoke a subtle resemblance to the Acropolis in Athens. The building exudes a blend of solidity and refinement, embodying a balance between grandeur and intricate detail. This artistic fusion is often seen in European public buildings, where the rational, restrained nature of neoclassicism complements the solemnity and seriousness required of a parliamentary space. The exterior alone is enough to inspire admiration, though unfortunately, we didn’t have the chance to explore the interior and appreciate its beauty firsthand.

Directly across from the Legislative Palace stands a crumbling wall covered in graffiti. Although Uruguay is considered one of the wealthier countries in South America, with a per capita GDP of around 17,000 USD, certain elements reveal a more relaxed and loosely managed character. Despite Uruguay’s reputation for discipline compared to its neighbors, the streets still reflect some of the region’s common traits—disorder, idleness, and a degree of neglect.

Montevideo itself is a compact city, with July 18 Avenue as its main thoroughfare. This avenue, named to commemorate the promulgation of Uruguay’s first constitution on July 18, 1830, is dotted with small plazas, street gardens, and statues of religious and historical figures. Street vendors crowd the sidewalks, and the atmosphere feels laid-back and down-to-earth. There’s a certain charm in this informality, which makes the city feel more human and accessible. Even our local guide, though struggling to explain things, radiated a lively spirit. I found myself really liking the old man, with his expressive face full of stories, despite not understanding a word he said.

Independence Square

Walking along July 18 Avenue, you will see the towering Palacio Salvo, a building completed in 1928. Although it is now just an ordinary apartment complex, it remains a significant landmark. From here, you reach Independence Square, where the equestrian statue of José Artigas, the leader of Uruguay’s independence movement, stands proudly. The statue aligns beautifully with the distant Palacio Salvo, creating a picturesque scene in the square.

The reliefs on the monument are especially striking, not focusing on war but on the migration of ordinary people. While horses and cold firearms appear in the imagery, the emphasis is on elderly people, children, and families, evoking a sense of warmth and humanity. The figures are vividly portrayed, bringing the narrative to life. Around the square, modern buildings dominate, indicating that this area belongs to the new part of the city.

Montevideo is divided into the new and old town sections, separated by the Independence Gate. Passing through the gate, you arrive at Constitution Square, where, in 1812, Spain’s first democratic constitution was read, ending the monarchy’s rule. As the square lacked a symbolic landmark, a European-style fountain was built, adorned with cherub statues. Strangely, the animals intertwined with the figures resemble Chinese dragons, a detail that remains puzzling. This fountain has since become the iconic centerpiece of Constitution Square.

Most of the surrounding buildings were constructed in the 19th century, including the Solis Theatre, Estévez Palace, and the Metropolitan Cathedral. Two pedestrian streets extend through the area, reflecting a distinctly Spanish style. Occasionally, the sound of a saxophone drifts through the streets, played by an old man sitting beside his worn-out bicycle, with fallen leaves swirling around him. The scene evokes the nostalgic atmosphere of an old European village, leaving a memorable impression.

Sarandí Pedestrian Street and Constitution Square

Sarandí Pedestrian Street is lined with vendors selling gemstones. One of the most notable features along the street is a bronze plaque depicting the famous “Sun of May.” The Río de la Plata region, shared by both Argentina and Uruguay, was the birthplace of the May Revolution, a movement that declared autonomy. On May 25, 1810, the first steps toward independence were announced. That day began under heavy clouds, but as the independence assembly progressed, the sky suddenly cleared, revealing the sun. This unexpected event was seen as a good omen, and thus the “Sun of May” became a symbol of the revolution.

To this day, both Argentina and Uruguay incorporate the blue and white stripes from the May Revolution into their national flags, along with the Sun of May as part of their emblematic designs.

Uruguay’s Famous Metropolitan Cathedral

Whenever I travel to a new country or city, I always enjoy visiting a church, as I believe churches hold cultural significance for a nation or people. In Montevideo, along the edge of Constitution Square, stands the Metropolitan Cathedral, one of Uruguay’s largest churches. Some sources refer to it as the “Matisse Church,” but this seems to be a misunderstanding. Henri Matisse, the French Fauvist painter, did design a chapel late in his life to honor a nun, but that was in France, unrelated to Uruguay.

The cathedral, built in 1726, features a simple neoclassical exterior. Inside, the dome arches gracefully in parabolic curves. The main altar houses three statues, with the central one likely being the Virgin Mary, while the crucifix of Jesus is displayed on the wall in the left hall. I noticed that most worshippers were praying before the statue of Jesus. The church also contains numerous side altars, decorated with ornate sculptures depicting stories and figures from the Bible. One that left a strong impression on me was a statue of Saint Joseph, Jesus’ foster father, holding the child. His expression is tender and loving. Saint Joseph, though a mere man, raised Jesus as his son, despite having no children of his own.

A beautiful white marble relief panel also caught my attention, featuring Jesus and his twelve apostles. Each apostle holds a sacred object, though I couldn’t identify all of them, and I don’t recall the Bible providing explicit explanations for these items. The one I recognized was Saint Peter, standing to Jesus’ left, holding two keys—symbolizing the keys to heaven and hell, given to him by Jesus.

As I continued observing, I noticed an elderly man with white hair, sitting motionless with his head bowed. His weathered face carried an air of sorrow, and I couldn’t help but feel a sudden wave of compassion for him, wondering what burden weighed so heavily on his heart.

The Port of Montevideo: A Panoramic View from the Ship

From the ship, you can take in a panoramic view of Montevideo, where the blend of historical buildings and modern skyscrapers reveals the city’s unique charm. Many articles refer to Uruguay as the “Switzerland of South America,” but I struggle to see the connection. Swiss landscapes are defined by snow-capped mountains, lakes, green meadows, and fairy-tale architecture—elements that Uruguay lacks. However, viewing Montevideo’s skyline from the cruise ship, with its mix of old and new, offers a glimpse into the city’s subtle allure.

It’s said that Portuguese explorers first discovered Montevideo, exclaiming, “I see a mountain!” which became the inspiration for the city’s name. Historical records mention that the mountain they saw was over 130 meters high. But scanning the horizon through my telephoto lens, I couldn’t spot any such mountain. The Salvo Palace, standing 100 meters tall, is right in front of me, but there’s no mountain in sight. The old saying “seeing is believing” rings especially true here.

Montevideo is, in fact, a quiet and unassuming city, much like how Uruguayan poet Borges described it: “A city that slips quietly away with time, like stars reflected in water. A door within time’s illusion, where streets lead to gentler yesterdays.” Though Borges longed for the light of dawn, our ship was already preparing to depart. As the brown waters, red cargo ships, and gray warships slowly faded from view, I couldn’t help but feel that this truly is a poetic city. May the light of day bless its gardens, for this is a place where poetry seems to live and breathe.