King’s Cross Station

London King’s Cross railway station is located in the heart of the city, right next to the charming St Pancras railway station to the west. King’s Cross has become a tourist attraction thanks to Harry Potter fans, as it is the station where Harry boards the train to Hogwarts. The station has embraced this by creating a fictional “Platform 9¾” next to the platforms to delight visitors.

St Pancras station serves as the main gateway for international trains entering London and is the terminus of the Eurostar. King’s Cross, on the other hand, primarily operates domestic routes to northern destinations such as Cambridge and Edinburgh.

We took the Underground from Tower Bridge station to St Pancras, and after coming up to the surface and crossing one street, we reached King’s Cross station. In terms of appearance, I personally think St Pancras station is more beautiful!

St Pancras Underground Station is the busiest in London, with the most transit lines passing through. The London Underground does not have fixed platforms, meaning trains from nearly all lines may arrive at the same platform. Therefore, when boarding, you must pay close attention to the arriving train’s line to avoid getting on the wrong one.

The exit of St Pancras Underground Station leads directly to the charming St Pancras railway station building. In front of the station stands the “Lovers’ Farewell” statue. St Pancras is the London terminus for the Eurostar international trains. From here, you can take trains to many cities across Europe, including France and Belgium.

The most remarkable feature of St Pancras railway station is its iron-red building. Due to its proximity and massive size, capturing the entire structure in one shot is challenging, even with the widest-angle lens.

King’s Cross railway station is just a street away from St Pancras railway station, and you can see it as soon as you exit St Pancras. King’s Cross owes its fame largely to the popularity of the Harry Potter series. Its most famous feature is the fictional “Platform 9¾.”

British Museum

The British Museum, officially known as the British National Museum, was one of our main attractions in London. The museum offers free entry to everyone, but online reservations are required in advance. If you queue on-site, entry is not guaranteed, as the museum has a daily visitor limit, and access may be denied once capacity is reached.

We made our reservation at the hotel, which offers this service to guests free of charge. Our reserved entry time was 11 a.m. When we arrived, we saw a long queue of visitors wrapping around the building, and we felt fortunate to have booked in advance.

The British Museum is located in Russell Square, north of New Oxford Street. It was founded in 1753 and officially opened to the public on January 15, 1759, becoming the world’s first national public museum. The museum’s main entrance features ancient Greek-style architecture, with eight large Ionic columns on both the front façade and the adjacent porticos.

The British Museum is the world’s oldest and one of the most magnificent comprehensive museums. It is also one of the four largest and most renowned museums globally, alongside the Louvre in France, the Hermitage Museum in Russia, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States. The British Museum houses numerous artifacts and treasures from around the world, with a richness and variety of collections that are rare among museums worldwide.

The museum’s collections are categorized primarily into the Egyptian Collection, the Greek and Roman Collection, and the Oriental Collection. However, it is worth noting that the origins of many of these artifacts are not entirely honorable. A significant portion of the collection was acquired through plunder during British military campaigns in the 18th and 19th centuries, with Egypt, Greece, and China among the major victims.

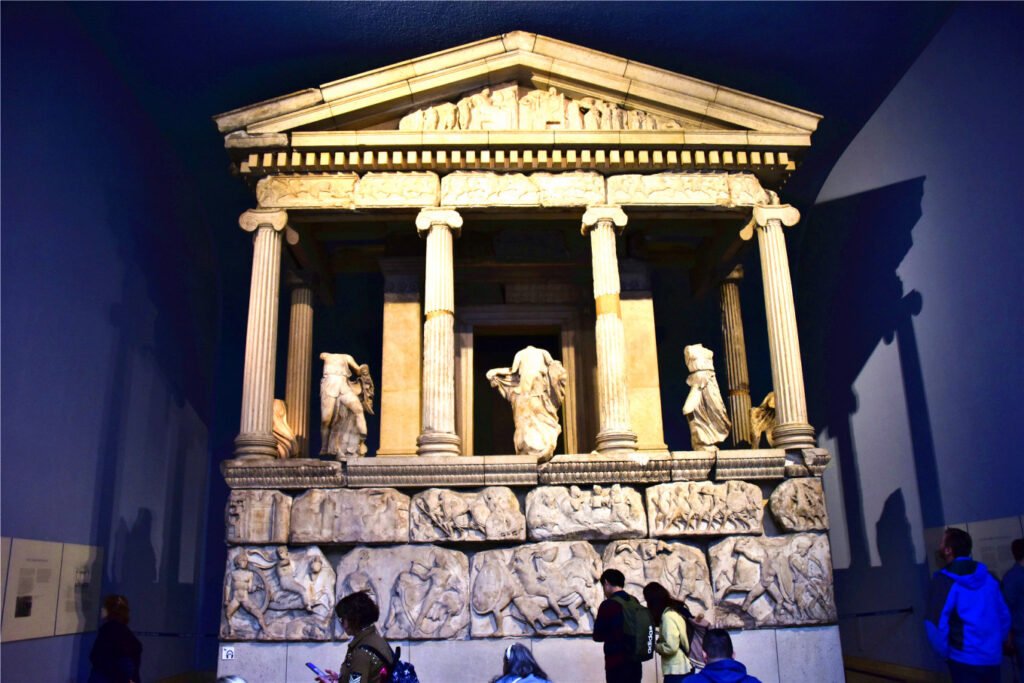

After entering the museum, we first visited the Greek and Roman Collections. To our surprise, much of the Parthenon in Athens had been moved to the museum. It is said that the temple’s remains were not looted but purchased by the museum for the incredibly low price of £35,000.

The Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon are renowned for their exquisite craftsmanship. Pay close attention to the intricate folds of the garments and the detailed muscle lines in the sculptures. These artifacts were acquired in 1816, and although Greece has since demanded their return, the British have refused to repatriate them.

The most famous exhibits in the Greek and Roman Collections also include two nude statues of Venus. One of them is the Crouching Venus. The brilliance of this statue lies in the fact that, although Venus is completely nude, her most intimate parts are concealed from every angle. It is said that the sculpture depicts Venus in a protective posture, shielding herself from prying eyes as she bathes.

The second part of our visit was to the Egyptian Collection. It is the largest gallery in the British Museum, housing more than 70,000 ancient Egyptian artifacts, second only to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The collection includes large statues of human-animal hybrids, numerous mummies, the world-famous Rosetta Stone, and models of pyramids and the Sphinx, with some items dating back 5,000 years. These treasures include ancient Egyptian artworks seized by British naval commander Nelson from the French King Napoleon in the 19th century.

One display features a black broken stele, measuring 1.14 meters tall and 0.73 meters wide. The fine inscriptions on it are still clearly visible, divided into three sections, each written in a different script. This 4,000-year-old stone has inscriptions in both ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and Greek on the front and back, making it the only artifact of its kind. Historians used it to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs, making it the crown jewel of the British Museum. It was named the “Rosetta Stone” after being discovered in Rosetta, Egypt.

After over 4,000 years, the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone remain intact—a miracle in itself. The story behind the Rosetta Stone is fascinating. From 1798 to 1801, Napoleon led a military campaign in Egypt, accompanied by over 100 scientists and archaeologists studying Egyptian culture.

In 1799, soldiers building fortifications in a small village called Rosetta in the Nile Delta accidentally unearthed a black broken stele with clear inscriptions. The accompanying archaeologists quickly recognized its significance and planned to ship it to France for further study. However, before the French could do so, Napoleon’s army was defeated by the British.

Under the terms of the surrender agreement, France was forced to hand over all artifacts excavated in Egypt to the British. The Rosetta Stone eventually found its way to the British Museum, where it remains to this day. Even now, the stone’s label bears the words “A trophy of the British Army.”

The Chinese Ceramics Gallery is one of four new galleries opened by the British Museum in 2008. The collection spans from the Han and Tang dynasties to the Ming and Qing dynasties, featuring blue-and-white porcelain, Jun ware, Tang sancai, and cloisonné enamel, all arranged chronologically and by region. It is likely the largest Chinese ceramics collection outside of China. The fact that the British Museum dedicated an entire gallery to Chinese porcelain reflects the significant influence of Chinese ceramics abroad.

Some items in the Chinese Gallery are not open to the public. For example, the Tang Dynasty copy of Gu Kaizhi’s Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies from the Eastern Jin period is only accessible to select experts. This artwork is the earliest surviving Chinese silk painting and one of the oldest works by a professional Chinese artist, holding a milestone status in Chinese art history. It has been a treasured piece in imperial collections throughout history.

Many exhibits in the Chinese Gallery are related to Buddhism, originating from various grottoes in China. On the central wall, there is a large mural from Dunhuang, spanning several dozen square meters. Although the cut marks are still visible, they do not detract from the ancient mural’s vivid colors and the stately grandeur of the three “sumptuous and full-bodied” bodhisattvas depicted within.

Hyde Park

Hyde Park is the largest of London’s Royal Parks and one of the city’s most famous. It lies just west of Buckingham Palace, separated from it by only one street. The park covers 2.5 square kilometers and is divided by the Serpentine Lake into two sections: Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. This vast expanse of greenery within the bustling city brings much joy to visitors.

Before the 18th century, the area was a royal hunting ground for deer, later transformed into a public park. The park’s most famous feature is Speaker’s Corner, a symbol of British democracy, where citizens can publicly speak on any topic of national or civic interest—a tradition that continues to this day. Hyde Park also hosts large open-air concerts almost every summer.

Wellington Arch

Wellington Arch is located on the southern edge of Hyde Park in London and is often referred to as the “Arc de Triomphe” of the UK. It was originally built to commemorate the Duke of Wellington’s victory over Napoleon during the Napoleonic Wars.

The Duke of Wellington, born Arthur Wellesley (May 1, 1769 – September 14, 1852), was a prominent British military and political figure, serving as a field marshal in the British Army and as the 21st Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

The arch was completed in 1826 but was not initially located here. In 1883, it was relocated to its current position due to road construction.

Atop Wellington Arch is a bronze quadriga, a four-horse chariot. Above the chariot stands a statue of Nike, the goddess of victory, holding an olive branch and a laurel wreath, symbolizing peace and victory. Originally, the arch was crowned with an equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington, but the statue’s disproportionate design sparked widespread controversy. After the duke’s death, it was replaced in 1912 by the current quadriga sculpture.

Even so, a new equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington was erected in Hyde Park as compensation. This statue now stands on the grass to the north of the arch.

Buckingham Palace

Following the Royal Artillery Horse Guards Parade path behind Wellington Arch leads to our final stop of the day—Buckingham Palace.

Buckingham Palace is the royal residence of the United Kingdom, located in the City of Westminster. It is a square, four-story building enclosing a courtyard. Originally built in 1703 by the Duke of Buckingham, it was named Buckingham Palace. In 1726, King George III purchased the palace and expanded it. In 1837, after Queen Victoria ascended the throne, it officially became the royal palace and has served as the residence of the British monarchy ever since. Today, it is home to King Charles III.

The London Eye

The London Eye is one of London’s most popular tourist attractions. It is located on the south bank of the Thames, facing the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben across the river. When it was built, it was the largest Ferris wheel in the world (though six others have since surpassed it). Standing at 135 meters tall, the London Eye is a modern landmark of the city.

Completed and opened at the end of 1999, it was built to celebrate the new millennium, earning it the nickname “Millennium Wheel.” At 135 meters, it rises above all surrounding buildings, offering a panoramic view of London from its top. As a new symbol of the city, the London Eye draws visitors across Westminster Bridge to the South Bank.

If you look closely, you’ll notice that the London Eye is mounted on the Thames rather than on solid ground, which significantly increased the difficulty of its construction.

Big Ben

Big Ben is located on the north bank of the Thames, directly facing the London Eye across the river. In my mind, Big Ben has become synonymous with London, much like Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the Statue of Liberty in New York, or the Eiffel Tower in Paris. It represents British classical culture, stands as a symbol of London, and is a source of pride for the British people.

Completed in 1859, the clock tower was named in honor of Benjamin Hall, the man in charge of the project, who was known for his large stature. Initially, “Big Ben” referred only to the 14-ton bell inside the tower, but over time, the name has come to represent the entire tower.

Since it began operating in 1859, the British government has maintained Big Ben every five years, including cleaning the clock and replacing the timekeeping and operational mechanisms.

Big Ben has long inspired the British people’s patriotism and bravery, becoming a symbol of London’s resilience. During World War II, despite thousands of air raids by the German Luftwaffe, Big Ben miraculously survived and continued to broadcast its reassuring chimes throughout the city.

Connected to Big Ben is the Palace of Westminster, home to the UK Parliament, including the House of Lords and the House of Commons. The clock tower is an integral part of the Palace, forming a unified whole.

As a masterpiece of the Gothic Revival style, the Palace of Westminster, along with the clock tower, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. The building complex contains approximately 1,100 individual rooms, 100 staircases, and 4.8 kilometers of corridors. Though much of the current structure dates back to 19th-century renovations, many historical elements from its original construction have been preserved.

Horse Guards Parade

The Horse Guards Parade dates back to 1745. It got its name because the Household Cavalry has been stationed here since its inception. The parade ground is the venue for major ceremonial events in London, including the annual Trooping the Colour ceremony, held to mark the British monarch’s official birthday.

Near the headquarters of the Household Cavalry is the British Army’s former administrative building. From the 17th century until 1964, the War Office was responsible for managing the British Army, after which its duties were transferred to the Ministry of Defence. During World War II, Field Marshal Montgomery worked from this building.

We noticed that the British Army does not carry the title “Royal,” unlike the other branches of the military. This distinction stems from the monarchy’s resentment toward the army for its role in overthrowing King Charles I during the mid-17th century.

St. Paul’s Cathedral

St. Paul’s Cathedral is a masterpiece of Baroque architecture, renowned for its magnificent dome and considered a symbol of British classical architecture. It is the largest cathedral in the UK and the second-largest domed church in the world, second only to the Cathedral of Florence in Italy. As one of the world’s most famous religious sites, it holds significant historical and cultural importance.

The original St. Paul’s Cathedral was built in 604 by the Anglo-Saxons using wood and named after the missionary Saint Paul. Since then, it has served as the seat of the Bishop of London. Over the centuries, the cathedral was repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt. The version we see today began construction in 1675 and took 35 years to complete, finally being finished in 1710.

St. Paul’s Cathedral is a must-see for visitors to London. Two well-known events held here were the wedding of Princess Diana and the funeral of “The Iron Lady,” Margaret Thatcher.

The main entrance of St. Paul’s Cathedral faces west, with a portico made up of six pairs of tall stone columns. On the pediment above the entrance is a carving depicting St. Paul preaching in Damascus (now the capital of Syria). At the peak of the pediment stands a stone statue of St. Paul. At both ends of the cathedral’s façade are two clock towers mirroring each other. The northwest tower houses a set of church bells, while the southwest tower holds a 17-ton bronze bell, the largest in England. The entire structure is precise, dignified, and grand, representing a masterpiece of British classical architecture.