Casablanca is the biggest city in Morocco and its economic hub, as well as an important port city. However, it’s not the capital—just like Sydney isn’t the capital of Australia. The capital of Morocco is Rabat (another low-key capital). Morocco has two official languages: Arabic and French. Generally, people with higher education speak French, while those with lower education only speak Arabic. But you’ll see most street signs in French.

Most of the restaurants here are French-style, with baguettes as the staple. They stuff everything into the bread, which ends up with weird-tasting sauces that might make you roll your eyes. So, whether you’re high or low, you’ll want to get a drink. Prices are similar to those in the Middle East or Turkey, but honestly, the food is pretty bad. I thought Turkey had the worst food, but Morocco taught me otherwise. Just my personal opinion.

On the streets, people sell cactus fruit, which I saw for the first time. I tried it, and it was pretty sweet and tasty. Actually, dragon fruit is just a type of cactus fruit, but these are smaller, with thicker skin, larger seeds, and sweeter. They cost 5 dirhams each.

Casablanca’s fame largely comes from the classic film “Casablanca.” Set against a backdrop of wartime turbulence, the film turned Casablanca into more than just a city name—it became a symbolic, dream-like icon. In reality, Casablanca is a city with a tumultuous history.

Records show that indigenous Berbers were active in the area and began shaping the city’s early form around the 7th century BC, making it an important port for the Phoenicians and later the Romans. In the 12th century, Arab tribes took over the city, known then as Anfa, and mixed with the local Berbers. In the early 15th century, the Portuguese invaded and destroyed the city, establishing a military fortress on the ruins, which they named Casa Branca. Later, the Spanish took over, and “Casablanca” became the Spanish translation of “white house” (Casa Blanca).

The 1755 earthquake led the Iberian invaders to abandon the city, which was then rebuilt by the Arabs and renamed “Dar Beida,” continuing the “white house” theme. In 1907, Casablanca fell under French colonial rule until it regained independence in 1956 and the name “Dar Beida” was restored.

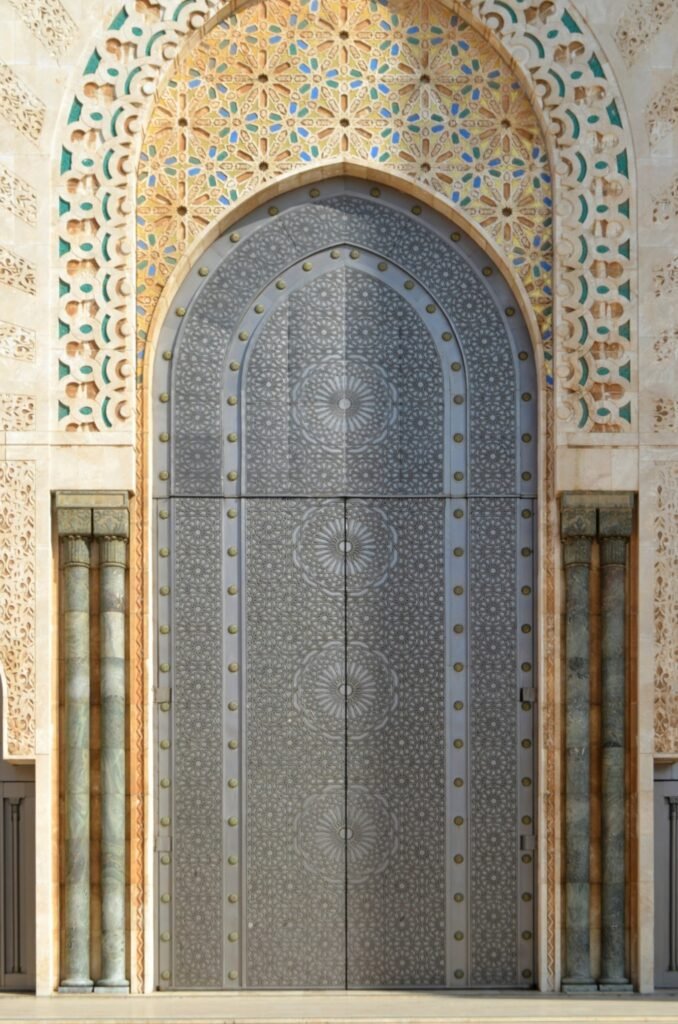

The most famous landmark in Casablanca is undoubtedly the Hassan II Mosque. This is the third-largest mosque in the world, and it showcases the talents of craftsmen from across the country who worked tirelessly on its construction. Work on the mosque began in 1987 and was completed in 1993, covering approximately 9 hectares, with one-third of that land reclaimed from the sea. Unlike many mosques, the Hassan II Mosque allows visitors to explore most of its areas, giving everyone the chance to experience the grandeur of this architectural marvel.

The Hassan II Mosque consists of two main sections: the main hall and the outdoor plaza.

In the past, if you visited Casablanca just to see the mosque’s exterior and didn’t plan to enter, you could stroll around the plaza and take photos without purchasing a ticket. However, since July 2022, the entire area surrounding the mosque, including the plaza, has been fenced off, and entry now requires a ticket. Otherwise, the mosque can only be admired from a distance.

Tickets are sold for specific time slots, with the last afternoon slot at 3 PM. When planning your visit, be sure to arrive early, purchase tickets on-site, and manage your time carefully—particularly for interior tours, as you must enter on time. If you miss your slot, you’ll either have to wait for the next one or risk missing the tour entirely.

The Hassan II Mosque is partially built on the Atlantic Ocean, with one-third of the structure extending over the sea. This is inspired by the belief that “the ancestors of the Arabs came from the sea.” Due to its unique location, the mosque’s doors are made from titanium alloy to resist corrosion from seawater and moisture. The interior floor is temperature-controlled, so even in winter, people won’t feel cold when walking barefoot. Additionally, the mosque’s roof can be opened, a process that takes about five minutes, though it can take longer in windy weather.

Beyond its high-tech features, the mosque is deeply traditional in design. Crafted by around 12,500 Moroccan artisans, it follows the tradition of handcrafted art with vibrant, colorful mosaics. Besides a small amount of marble and lighting imported from Italy, all other materials are sourced locally in Morocco. The building is predominantly white with green accents, presenting an imposing and beautiful exterior. Inside, the materials are carefully chosen and intricately detailed, reflecting true craftsmanship. It stands as a proud landmark of Casablanca and Morocco.

Most of Casablanca’s buildings are white—white mosques, white train stations, and white cafés—all shining brightly under the abundant sunlight. The contrast between these white structures and the deep blue Atlantic Ocean creates the dazzling image of the White City that lingers in my mind.

This modern metropolis perfectly balances tradition and progress. As you navigate its bustling streets, you’ll be captivated by the harmonious blend of historical landmarks and contemporary architecture.

Miami Beach Avenue is Casablanca’s hub of indulgence, filled with cafés, restaurants, and clubs. Of course, there’s also a long beach where, regardless of the season, you’ll always find people swimming, playing football, or simply gazing at the ocean.

Walking through the streets of Morocco, you’ll notice a striking feature: a sea of Mercedes taxis. It might seem surprising that a country in Africa, no matter how wealthy, could use luxury cars for taxi services. Yet, that’s exactly the case here. These Mercedes taxis are genuine but second-hand, brought to Morocco after being retired in more developed countries. Fuel-inefficient models are avoided, and the focus is purely on practicality, much like the old Volkswagen Santana, known for being sturdy and durable.

Some of these Mercedes taxis date back to 1976, and many have clocked millions of kilometers but continue to roam the streets, a testament to their reliability.