Leipzig is a renowned historical and cultural city in eastern Germany, the capital of Saxony, and the second-largest city in what was once East Germany. It’s also known as the “Little Paris” in Goethe’s writings, with its rich and long-standing history still shining brightly today.

The name Leipzig comes from “Lipsk,” which means “linden tree.” In the bustling area around Augustusplatz, you can still see many linden trees. Among them are several special rows marked with signs bearing names, most of which are planted by friends and family in memory of the deceased. One tree, in particular, catches the eye from a distance with its colorful array of objects placed beneath it, creating a lively scene that draws you in for a closer look. Upon closer inspection, you’ll be amazed to discover that this tree was planted by fans of Michael Jackson in his memory, honoring the legendary artist in this heartfelt way.

Today, Leipzig is celebrated for its rich history and culture, but three to four centuries ago, it played a crucial role in the development of trade and commerce in Europe. The flourishing printing and publishing industry here not only attracted a large number of writers and musicians but also boosted the city’s economic standing. For a long time, Leipzig was the center of Europe since goods needed to be insured and registered here.

In addition to having the fifth-largest stock exchange at one point, it was also the city with the most train platforms in Germany before World War II. The annual book fair has been a significant highlight for Leipzig, even though it has been surpassed by Frankfurt in recent years.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, East and West Germany became one, and people’s movements became free and unrestricted. However, this also led to a significant population drain from many East German cities, including Leipzig. It’s said that the government implemented a policy to retain residents and attract new “migrants,” stating that “settling in Leipzig only requires paying utility bills,” implying that rent and other costs would be covered by the government. Unfortunately, this initiative didn’t yield the desired results.

In recent years, Leipzig’s population growth has been fueled by the arrival of several major companies, earning it the “honor” of being one of the cities in Germany with the highest birth rates.

Literary Flourishing

Starting in the 16th century, with the gradual rise of the printing and publishing industry, many world-renowned writers and artists came to Leipzig to publish their works. Fast forward a few hundred years, and while printing and publishing can now be found in every corner of the globe, the figures who once hurried, searched, or found solace in this city shine even brighter in our memories, making Leipzig a place forever celebrated for its literary heritage.

The famous literary giant Goethe studied law at Leipzig University. Although he spent only about three years in the city, and his time there was not particularly smooth—he ultimately dropped out due to health issues—this didn’t diminish the “Goethe imprint” he left on Leipzig.

In the city center stands a statue of Goethe, with the former bustling stock exchange site behind him and a small square in front occupied by an outdoor café. On sunny days, you can order a cup of coffee and sit outside, enjoying a moment of eye contact with “Goethe.”

Additionally, there’s a famous restaurant in the city center that Goethe frequented. The young Goethe was not particularly focused on his studies at the time; instead, he was more interested in drinking and gathering materials. It’s said that this very restaurant inspired him to write “Faust,” and despite undergoing several renovations over the past few hundred years, it still retains the ambiance described in “Faust.” To highlight its uniqueness, the restaurant has two statues outside representing the two main characters from “Faust”: Faust and the devil Mephistopheles. Many tourists, even if they don’t dine inside, make sure to stop by the restaurant entrance to take photos as a keepsake.

City of Bach

In contrast to the briefly visiting young Goethe, several world-renowned musicians patiently composed their masterpieces here. Leipzig is also known as the “City of Bach.” This great composer of the 17th and 18th centuries started as a young organist and eventually became the choral director at St. Thomas Church, spending the most glorious and final 27 years of his life in Leipzig.

Bach was an incredibly prolific musician, with a body of work totaling around 200 hours of music. To put that into perspective, if we consider contemporary pop songs to be about 5 minutes long, Bach composed roughly 2,400 pieces throughout his lifetime! Such an impressive record remains unmatched even today. Additionally, his two wives gave him more than 20 children, showcasing another aspect of his “prolific” nature.

Bach worked at St. Thomas Church for 27 years and was buried there, making it feel like home to him.

In front of St. Thomas Church stands a statue of Bach, with a serious expression and piercing gaze. It turns out that nearly all depictions of Bach, whether portraits or sculptures, reflect this same demeanor, as it is said to mirror his own character—stern and even somewhat harsh, with almost no smiles, especially when it came to his meticulous attention to detail in music.

However, in sharp contrast to his musical precision, he was quite relaxed about life’s little details. This is evident in the statue, where one of the buttons on Bach’s coat is left undone, adding a touch of lightheartedness to his otherwise serious image. Bach’s reputation and the hard work he put into his 27 years in Leipzig cast a lasting glow over the city. Because of this, Leipzig is often referred to as the “City of Bach.” Many souvenirs feature his likeness, and even the Meissen porcelain shop offers a special edition plate dedicated to Bach, which is so popular that it frequently sells out.

Not far from St. Thomas Church, there’s a Bach Museum. While it’s not very large, it chronicles significant events in Bach’s life, allowing visitors to gain a more systematic and intimate understanding of this great musician. The museum showcases Bach’s manuscripts, and guests can even use high-tech methods to listen to his works on-site.

On the first floor of the Bach Archive, there’s a gift shop, and adjacent to it is a café that is part of the museum. The coffee and pastries there are quite tasty, making it a nice spot to relax after exploring the exhibits.

A Shining Array of Stars

In addition to the deep imprint left by Bach on Leipzig, many other exceptional musicians have called this city home, including Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Wagner.

Since you’re in Leipzig, you shouldn’t miss the chance to visit their former residences. Although these world-renowned musicians have been gone for over a century, standing in the places they once frequented makes you feel a sense of wonder and luck, imagining that they stood there two hundred years ago.

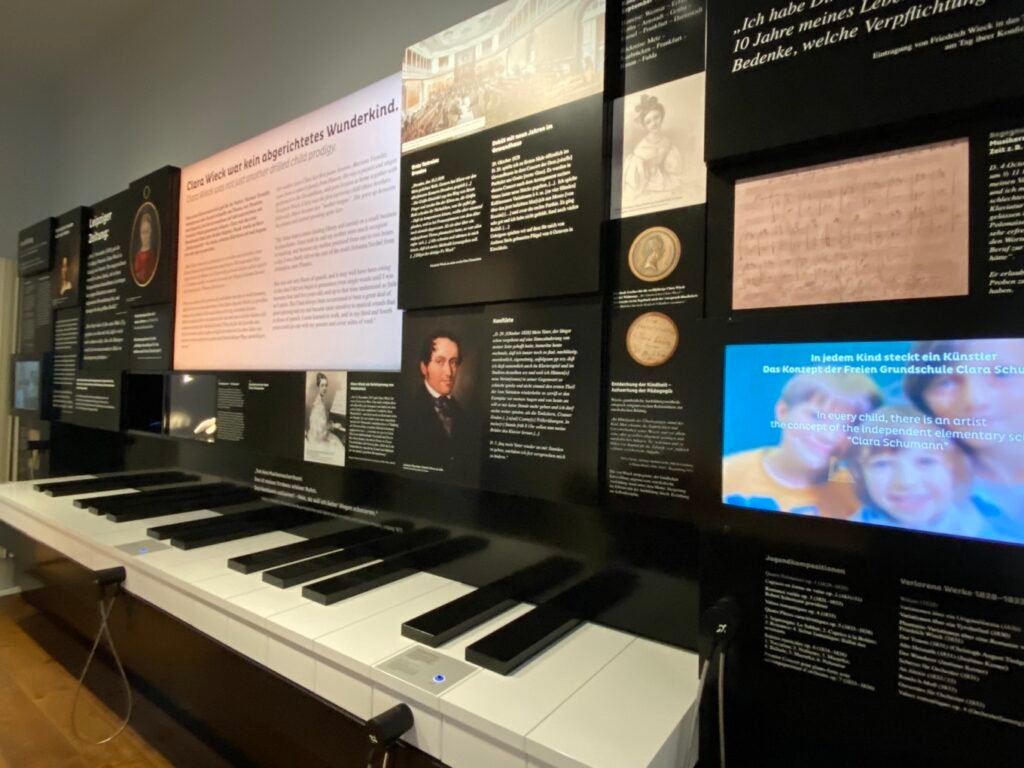

Schumann’s house is relatively small and integrated with a music education institution, making it somewhat of an “off-the-beaten-path” destination. After entering the gate, you have to climb a staircase that seems quite old, creaking as you go—one can’t help but wonder if it made the same sounds when the Schumann couple lived there. On a sunny weekday afternoon, the entire house is incredibly quiet, with just me there, allowing me to leisurely enjoy the story of Schumann and his wife Clara without any distractions.

One story that left a lasting impression on me is about the Schumann couple’s trip to Russia for a concert in the early 19th century, a time when transportation and communication were quite limited. After a long and bumpy journey, they finally arrived but were mistakenly taken to a shabby inn with poor conditions. The Schumanns had no choice but to endure this discomfort until they could change accommodations the next day. Unlike today’s musicians, who often specialize in their craft, back then, they had to coordinate and arrange almost everything themselves, even though they are viewed as brilliant musicians by posterity.

The Schumann residence also features a high-tech display that simulates Clara taking the stage to perform. When visitors put on headphones, they see a technician leaving his seat as he adjusts the piano, followed by a round of applause. Clara then appears to acknowledge the audience, gracefully playing the beloved “Spring Song.” The melody is sweet and flowing, and as she bows amid the applause and flowers, she smiles and elegantly exits the stage. For a moment, I was transported; even though I knew it was a technological simulation, it felt incredibly magical to encounter Clara across time.

Compared to Schumann’s residence, Mendelssohn’s home is much more spacious and lively. Mendelssohn was a piano prodigy, displaying exceptional musical talent from a young age and receiving a top-notch education. What surprised me was the number of delicate and vividly colored watercolor sketches hanging on the walls of his home. Upon closer inspection of the descriptions, I learned that Mendelssohn was not only a gifted composer but also a skilled painter. Whenever he traveled to places like Switzerland, he would use his brush to capture the beautiful scenery, showcasing his talent as a true polymath.

However, it seems that fate was unkind to such a brilliant individual. Mendelssohn passed away at the young age of 38. In addition to his contributions to music composition and performance, he invented the conductor’s baton and founded Germany’s first music academy—the Leipzig Conservatory—which continues to nurture talent for future generations.

Leipzig not only boasts a glorious musical history but also continues to be a hub for music students and enthusiasts today.

On the streets of Leipzig, you’ll often encounter many bands and even piano duets playing with such skill that you can’t help but stop to enjoy the performance, willingly reaching for your pockets to toss in some coins. Furthermore, Leipzig’s central train station is the only one I’ve seen that plays classical piano music, blending everyday life with a touch of elegance.

As you walk the streets of Leipzig, you might occasionally glance down to see crescent-shaped symbols on the ground. These marks indicate nearby significant music-related landmarks for tourists.

In addition to the homes, museums, and churches where musicians once worked, there’s also the opera house located at Augustusplatz. The opera house we see today was built during the East German period and is the third opera house in Leipzig’s history, as the first two were destroyed due to wars and other reasons. In a culturally rich city like Leipzig, having an opera house is essential for soothing the minds and souls of its people.

There’s a humorous saying that regions with a strong artistic atmosphere tend to have high levels of economic development, yet Leipzig stands out as a place where, even without great wealth, opera, music, and ballet remain indispensable. The fountain in front of the opera house, built in 1886, remarkably survived the wars, making it a rare gem.

Leipzig University, founded in 1409, is the second oldest university in Germany. This historic institution has not only produced notable figures like Nietzsche, Goethe, Schumann, and Merkel but has also been the alma mater of several Nobel Prize winners. Among its distinguished alumni are several prominent Chinese figures, such as Gu Hongming, Cai Yuanpei, and Lin Yutang.

In addition to its ancient history and illustrious background, Leipzig University boasts a highlight in the newly completed Paulinum building on its campus, which was finished in 2017. This building is located on the site of the old Pauliner Church, the only church that remained intact during World War II, only to be demolished by the East German government in 1968.

Unlike traditional churches, as you look at the Paulinum, you are greeted by a stunning expanse of green glass, which seems to modernize and shake up memories of the past in a fresh and innovative way.

Tips (The following recommendations do not contain any commercial promotions):

Walking Tour: If you’re interested in history and culture, I personally believe that joining a local walking tour is the best way to get an initial feel for a city. You’ll not only gain insight into its history but also hear some lively and interesting stories or anecdotes. There are various themed tours available, and free tours rely on tips for income. If you enjoy the tour, a tip of around ten euros is a reasonable baseline (of course, this is voluntary and can vary based on the group size).

Dining in Leipzig: The restaurant mentioned in the text, Auerbachs Keller (related to “Faust”):

- Address: Grimmaische Straße, Mädler-Passage 2-4, 04109 Leipzig

If you enjoy German cuisine, be sure to give it a try. Although it’s a popular spot and can get busy, it’s a century-old establishment with reasonable prices, and you can check out part of the menu on their website.