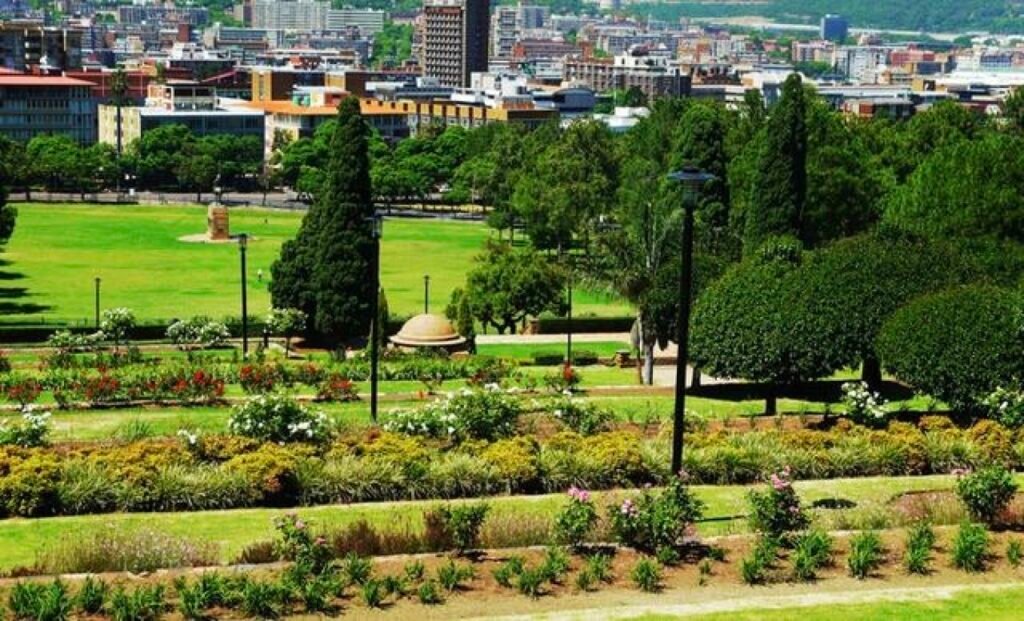

The South African Presidential Complex is situated on a hill that overlooks the entire city. It’s an impressive European-style building with a curved, grand design that resembles a huge theater, exuding a sense of solemnity and grandeur. The structure is made of beige granite, with a red-tiled roof, giving it a majestic appearance from afar. In front of the building is a vast terraced garden adorned with monuments, statues, lawns, and flower beds, creating a beautiful landscape that is both refreshing and soothing.

On March 7, 2005, South Africa’s administrative capital Pretoria adopted a resolution to restore its original name, Tshwane, while retaining the name Pretoria for the central city area. This name change was intended as a significant symbol of breaking away from the apartheid era. The South African Presidential Complex, designed by Sir Herbert Baker, is a majestic granite building. It sits on a hill in Pretoria, offering a panoramic view of the city. The front of the building features well-maintained gardens with various monuments and statues. The rear of the building is surrounded by extensive forests and shrubland, home to many bird species.

The Union Buildings were designed by Sir Herbert Baker and completed in 1913. Situated on a hill in Pretoria, the structure forms a sweeping arc, with its façade made of light beige granite and topped with red-tiled roofs, creating an elegant and majestic appearance from a distance. In front of the buildings lies a grand terraced garden, adorned with monuments, statues, lawns, and flower beds, painting a beautiful landscape.In 1994, Nelson Mandela, the Black leader who dismantled apartheid, was inaugurated here as South Africa’s first Black president, marking a historic moment for the country.

In front of the Union Buildings stands a monument topped with a statue of two people holding the reins of a tall horse. This symbolizes the shared effort of the British and the Boers to govern South Africa together. It is a clear indication that, at that time, Black South Africans had no political standing.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (July 18, 1918 – December 5, 2013) was born in Mvezo, South Africa. He earned a Bachelor of Arts from the University of South Africa and a law degree from the University of Witwatersrand. Mandela served as the national secretary and president of the African National Congress Youth League. From 1994 to 1999, he was the President of South Africa, becoming the country’s first Black president and earning the title “Father of the Nation.”

Before his presidency, Mandela was a prominent anti-apartheid activist and the leader of the armed wing of the African National Congress, Umkhonto we Sizwe. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1962 on charges of conspiring to overthrow the government and served 27 years in prison. After his release in 1990, he supported reconciliation and negotiation and played a key role in leading South Africa through its transition to a multiracial democracy. Since the end of apartheid, Mandela has received widespread praise, even from former opponents. He passed away at his home in Johannesburg on December 5, 2013, at the age of 95.

Over 40 years, Mandela received more than a hundred awards, with the most notable being the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. In 2004, he was named the greatest South African.

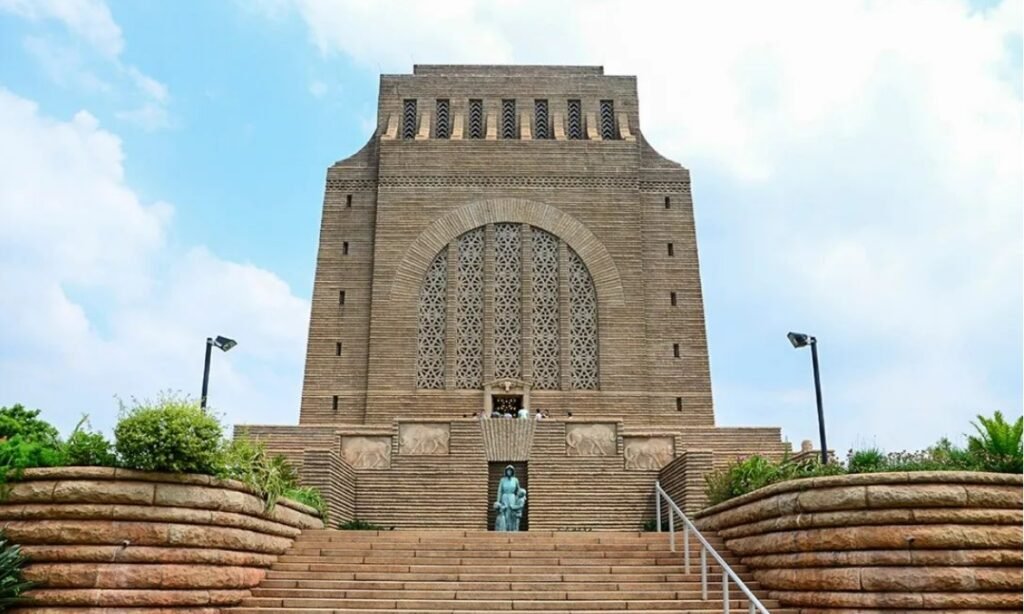

At the suggestion of South Africa’s first president, Paul Kruger, the Voortrekker Monument was built in 1960 on a hillside in Pretoria. The structure stands 41 meters high with a cubic design. At each corner, granite sculptures depict three Voortrekker leaders and an unknown hero holding a rifle.

Who were the Voortrekkers? They were the Boers, a white ethnic group in Africa formed primarily from Dutch settlers who immigrated to South Africa between the 17th and 19th centuries, later integrating French and German migrants. Most Boers adhere to Protestant Christianity, with a minority following Catholicism. According to a 2001 census, their population stood at approximately 2.5 million.

On December 16, 1838, migrating Boers defeated Zulu King Dingane and seized large portions of inland South African territory. This date became known as “Dingane’s Day” or “Day of the Vow.”

After the establishment of the new South African government in 1994, President Nelson Mandela did not order the demolition of this monument to the white pioneers. Instead, it was preserved as a site for tourism and education. However, the holiday was renamed “Day of Reconciliation” to promote the idea of peaceful coexistence between South Africa’s Black and white populations. Today, many white South Africans visit the Voortrekker Monument to reflect on their history and express their desire to live in harmony with the Black community.

After climbing the steep steps leading to the monument, visitors can stand before this imposing structure.

After climbing dozens of steps, we entered the Hall of Heroes on the first floor of the monument. In the center of the hall is a large circular opening, several meters in diameter. Standing at the edge of the opening, you can see down to the lower level, where a rectangular granite sarcophagus is placed at the center.

At the top of the hall’s dome, there is a small aperture. Every year, on December 16th at precisely noon, sunlight streams through this opening, shining directly onto the tombstone below. Inscribed on the tombstone are the words of the Voortrekkers: “South Africa, we are willing to sacrifice for you.”

The hall is divided into upper, middle, and lower levels. On the walls of the middle level, 27 marble reliefs are embedded, each depicting a complete story from the Boer Wars. The Boer Wars were fought between the British and the Boers over control of South Africa’s colonies. There were two Boer Wars in history: the first from 1880 to 1881, and the second from 1899 to 1902.

On May 31, 1902, realizing they could not eliminate the Boers, the British signed the Treaty of Vereeniging, recognizing British sovereignty over the Boers but guaranteeing their personal freedoms and property rights. The treaty also provided financial assistance to help the Boers rebuild their homes and establish self-governance. Although the British emerged victorious, the Boer Wars marked the decline of the British Empire. European powers widely condemned Britain’s policies in South Africa, accusing it of greed for gold and mistreatment of the two small Boer republics. The war triggered significant changes within the empire, earning it the reputation of being the “War of the British Empire’s Decline.”

The monument also recounts the Battle of Blood River, which took place on December 16, 1838. This battle was fought between over 12,000 Zulu warriors and 470 Boers participating in the Great Trek. It occurred along a tributary of the Buffalo River, and the river turned red with the blood of 3,000 fallen Zulu soldiers, giving the battle its name.

On November 20, Boer leader Andries Pretorius led the Boers and 57 ox-drawn wagons, along with two small cannons, as they began their migration. On December 15, the Boer vanguard encountered Zulu scouts. Pretorius formed a defensive laager at the bend of the Ncome River, linking the wagons in a circle and filling the gaps with thorn bushes. The wagon wheels were lashed together with ox hide to strengthen the formation.

Sheltered within the laager, the Boers continuously fired their guns and cannons. Zulu King Dingane hesitated to attack at night—when the Boers were most vulnerable—and delayed his assault until the next morning. Despite their courage, the Zulu warriors were unable to engage the Boers in close combat, their numbers rendered useless against the Boers’ superior firepower. Wave after wave of Zulu fighters fell before the laager, suffering heavy losses. Eventually, Dingane ordered a retreat, but Boer cavalry pursued and crushed the retreating Zulu forces.

The battle ended with 3,000 Zulu casualties, while the Boers lost only three men—a staggering ratio of 3:3,000. The spears of the Zulu warriors were no match for the firearms and cannons of the Boers. With this victory, the Boers secured their place in the region.

The museum also features exhibits showcasing scenes from the Voortrekkers’ daily life as they migrated inland across South Africa.

South Africa’s ability to transition from a racist regime to a new society without widespread bloodshed, achieving a relatively peaceful transition, owes much to the efforts of De Klerk and Mandela. In 1993, the Nobel Peace Prize was jointly awarded to Mandela and De Klerk in recognition of their work.

In Pretoria, one can sense the weight and suffering of South Africa’s history. However, that chapter has now closed, and a new South Africa is on the rise.